|

||

|

|

||||

|

|

|||||

|

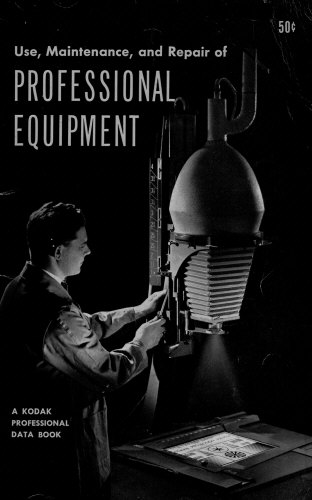

Professional photographers and a growing number of advanced amateurs who wanted more personal control over film processing and print making represented a market for photographic paper and chemicals that Kodak was glad to exploit and Kodak's market for photosenstitive materials and chemicals grew to accomodate users from Boy Scouts to large industrial users. By the period covered by this site--the last half of the 1930s through the mid-1950s--Kodak was the major supplier of home and small business darkroom equipment. Even small communities had at least one portrait photographer, providing a broad market for view cameras, enlargers and other film processing and printing equipment. Quality commercial images required large format equipment--at least 4 x 5, and most studios used 5 x 7 and 8 x 10 cameras for portaiture. These negatives required large enlargers, like the Eastman (Kodak) Auto Focus enlarger, shown at the left. By the late 1940s, Kodak offered a varied range of enlarger equipment for small commercial and home darkrooms. The down-sized, less expensive home units often benefitted from features and quality standards in the commercial line made possible by the large scale production of the line for home darkrooms. | ||||

| Post WW II hobbyists typically

worked with three film formats--35mm, 120/620 and 6 x 9 and 4 x5

sheet film. Kodak had traditionally made wood framed enlargers, but during

the Kodak Golden Age, Kodak migrated to metal construction in both professional

and amateur enlargers. From roughly 1940 to 1950, there were several enlarger

models to attract the hobbyist. |

|||||

10/28/2010 4:48 |

|

||||