| |

|

|

|

| |

When selling cameras and accessories

by auction, the buyer must rely on the seller's description. Many after-auction

conflicts are based on differing opinions about the condition of equipment.

Buyers can avoid useless returns or the need to haggle by evaluating sellers'

descriptions and asking questions to supplement published information,

knowing what to look for. Sellers can minimize negative feedback and requests

for external arbitration by carefully evaluating equipment condition and

describing it clearly. Lenses and shutters are especially problematic

because, even some experienced photographers may not have had experience

with some kinds of lens and shutter problems. Younger photographers may

not have experience with older kinds of equipment. Here is some help that

was originally written for old Kodaks, but is generally applicable to

most lens and to between-the-lens shutters that are not coupled to film

winding mechanisms. This holds true for most Graphic press, view and Graphic

XL cameras; Graflex reflex cameras have barrel lenses and focal plane

shutters that have very different controls.

Note: While I hope this page

serves an educational function, it also serves a certification function.

Auction sellers, if I refer you to this page for evaluation of lens and

shutter condition and you certify that your lens is free from defects

and that your shutter has certain reliability and accuracy, I consider

that you have reviewed this material and that review is part of our transaction--your

initial description, my questions, this review, and your answers.

This page is

written for sellers that have significant experience with cameras; here

is a similar page for those with less experience.

|

|

|

| |

How

to Evaluate Lens and Shutter Condition

Sellers, carefully

clean your lens before looking for problems and

photographing it for your auction. You can't accurately evaluate the condition

of a dirty lens and shots of dirty lenses make a bad impression on potential

buyers and at a minimum invite unnecessary questions. You will need a

bright light source and some kind of magnification to reliably evaluate

the condition of lens surfaces. A jeweler's loupe, photographer's loupe

or a common magnifying glass all will work. Buyers can use these same

techniques to examine equipment on arrival to see that it measures up

to sellers' descriptions.

Potential optical

problems include:

- Scratches

on glass surfaces, typically on the external surfaces of the front and

back lens elements. Examination of these surfaces, after careful

cleaning, under a bright light viewing the

lens at different angles is the best way to see scratches. Describe

what you see in your evaluation. Types of conditions:

- Scratches

where both the coating and glass are scratched. Size and position

are important factors to mention. On which lens elements are the

flaws located?

- Coating

problems. Sometimes overambitious cleaning will mar the coating,

but not the glass. Again, size and position are important, but also

the percentage of the surface of the element that is affected.

- Bubbles

in lens elements look dramatic, but have little or no effect on

image results. Bubbles were common in Kodak glass in the '30s-50s.

If a lens passed Kodak quality control it was probably OK.

|

|

|

| |

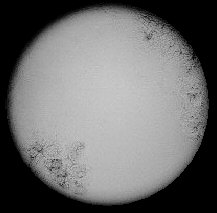

- Other lens

problems are better seen by looking into an illuminated lens using a

light source shown to the right. You should open the shutter and set

the lens to full aperture. Set the shutter on T or B.

|

|

|

|

| |

- Old lenses

sometimes are attacked by fungus. This will tend to appear as

a cloudiness or a frost-like pattern on glass surfaces. Sometimes it

will have a crystalline appearance. This can be on the exposed surfaces--front

or back of lens--or on the inner surfaces. This is a serious problem

if it has spread too far and etched the coating and/or glass.

- Lenses are

usually made from multiple pieces of glass, with some pieces cemented

together. When the adhesive fails, separation occurs. In

some lenses this will appear as cloudiness, generally around the perimeter

of the glass where the adhesive has failed. In modern, multicoated lenses,

this will generally appear as a reflective area in an otherwise transparent

element. The best way to see this is to move a lens under a fixed light

source; the problem will be very apparent at certain angles; be sure

check the both front and back lens elements. Look

for for separation by viewing through all of the lens elements, but

also through the ones closest to you toward the interior of the lens

barrel, for example, as the picture to the right is oriented. The damage

shown here looks like two pieces of wet glass held together by surface

tension, but where air pockets have gotten trapped between them.

- Many of

these conditions can be repaired, but only at substantial cost because

complex operations

similar to those used in lens manufacture have to be replicated. Lenses

can be polished and recoated to fix scratches and fungal damage. Separated

elements can be cleaned and relaminated. For the lens to perform at

or near its original specifications, care, expertise and special equipment

are required. This comes at between $125-200 per lens group, so such

repairs are usually only practical for expensive lenses.

- Scratches,

fungus damage and separation affect value to collectors and photographers,

pretty much in proportion to the seriousness of the flaws.

- Effects

of these flaws on lens performance is a subject of active debate. Flaws

near the perimeter of the lens will generally affect performance only

when the lens is set to or near its maximium aperture. Most of these

flaws cause light defraction--a scattering of the light rays--and reduce

contrast. The seriousness of this varies pretty directly with the amount

of the surface affected. Protecting the lens from light other than that

reflected by the field of view can reduce refraction, so using effective

hoods and multicoated filters is especially useful with flawed lenses.

|

Lens with a

fungal infection

A multicoated

lens with serious separation problems

Recementing

operation at S. K. Grimes

|

|

|

| |

- Many old

Kodaks cameras have lenses that are focused with a rotating front lens

element, with a protruding pin that limits rotation. This rotation is

normal and isn't a fault. Lenses for Graphics or other press or view

cameras generally do not have front cell focusing and have a fixed front

lens element, though they have similar kinds of lenses and shutters.

|

|

|

| |

|

- Shutters

may be dirty or broken. Most shutters on old Kodaks and Graphics have

to be manually 'cocked' before they will open. Most shutters have a

lever on the top in location

,

which, when moved in the direction shown, will cock the shutter; Graphic

XL lenses have the cocking lever on the bottom. The shutter release

on most Kodaks and Graphics is the lever in location ,

which, when moved in the direction shown, will cock the shutter; Graphic

XL lenses have the cocking lever on the bottom. The shutter release

on most Kodaks and Graphics is the lever in location  and should be pressed in the direction shown to trip and open the shutter.

These levers may look different or be in slightly different places,

but they generally operate in the same way. Some cameras will have a

body release, usually a button on the top of the camera, that is linked

to the shutter release lever. It is possible that the shutter itself

may work, even if the body release does not.

and should be pressed in the direction shown to trip and open the shutter.

These levers may look different or be in slightly different places,

but they generally operate in the same way. Some cameras will have a

body release, usually a button on the top of the camera, that is linked

to the shutter release lever. It is possible that the shutter itself

may work, even if the body release does not.

- While you

cannot check the accuracy of a shutter without special equipment, you

can see if all of the speeds work. By looking into the lens while you

are tripping the shutter, you will see the shutter blades open and close.

As you operate the shutter over its range, you should be able to notice

that as the shutter speeds get longer, the shutter stays open increasingly

longer. If you can see a pattern of increasingly longer durations the

shutter is probably operating correctly, though not necessarily that

each speed is accurate.

- Oil from

the shutter mechanism may have found its way onto the shutter blades

and must be removed or it may foul the lens. Leave this for the auction

winner or a technician, but it should be mentioned to the bidders.

|

|

|

| |

Cleaning

a Lens

Most old cameras

will have accumulated dust and maybe grime. Unless you have experience

with cameras, you may do more harm than good in cleaning other than a

light dusting. A vacuum cleaner with a clean dusting attachment is good.

To evaluate the lens, however, you will need to clean the exposed external

surfaces. This at least means the front of the front lens group and the

back of the back lens group. In many cases, with lenses on press and view

cameras, the groups can easily be removed from the shutter body so that

the rear of the front group and the front of the rear group can also be

cleaned.

- With a soft

clean brush, remove as much loose dust as possible. (An

unused cosmetics brush works well)

- Cleaning

with liquids should be a rinsing not a scouring operation. You are using

the liquid to dissolve oils on the surface of the glass. Rubbing is

abrasive and can easily scratch the relatively soft coatings on early

lenses.† Moisten a small piece

of tissue (white, unscented toilet tissue or facial tissue) or optical

tissue with lens cleaner or Windex and swab the lens surface. Let the

cleaner dissolve oils on the surface, then absorb the excess moisture

with a dry corner of the tissue. Repeat this operation with new tissue/lens

cleaner until you see no traces of oily film on the lens surface. Then

wipe it dry with a piece of optical tissue, which has less lint than

facial or toilet tissue. .A lens with accumulated oil/grease may require

6-8 repetitions. With folding cameras cleaning the rear lens element

is easy with the front closed and the back open.

- Never try

to clean a lens with dry tissue.

- After you

have shaken out any dust, brush away any tissue lint with the soft brush

or blow it away with the kind of syringe used to clean out babies ears.

An unused syringe, please.

|

|

|