| |

|

|

|

|

| |

CAVEATS

- All lens cleaning should be done

very carefully. Use only photographic lens cleaning fluid, Windex

or one of a select group of alcohols, and optical tissue or white, unperfumed

facial or toilet tissue. Remove fingerprints as quickly as possible.

Never use any kind of abrasive on a lens.

- The

conservative view is that only photographic lens cleaning solution,

with the correct pH balance, is safe for lens coatings. Similarly facial

or toilet tissue may be safe for the functions intended, but may contain

substances that can interact negatively with lens coatings.

- Kodak's advice was: "An

occasional cleaning of both rear and front lens surfaces is necessary.

Care should be used not to scratch these lens surfaces while cleaning

them. Any dust or grit should be removed first by gently brushing the

surface with wadded Kodak Lens Cleaning Paper or a fine camel's-hair

brush. If this brushing action fails to clear the lens, wipe it gently

with a wad made from one or several sheets of Kodak Lens Cleaning Paper

or a clean, soft, lint-free cloth, such as well washed linen. In the

case of fingerprints or any other grease or scum formation, the use

of a drop of Kodak Lens Cleaner on the cleaning paper or cloth or breathing

on the lens is suggested. Do not use acid, alcohol, or other solvents

or harsh, linty cloth. Avoid excessive cleaning and excessive pressure,

as they may do more harm than good."†

- One expert

suggests that only disposable brushes made from paper tissue be used,

since regular lens brushes inevitably pick up contaminants.

suggests that only disposable brushes made from paper tissue be used,

since regular lens brushes inevitably pick up contaminants.

- A small syringe, like the ones

used to rinse human ears, can be used as a source of clean dry air to

blow dust from lens elements. Best to have separate syringes for ears

and lenses.

LENS COATINGS

- Before the mid 30s, lenses had

no commercially applied coatings

.

Although the effect of lens coatings was observed a couple of decades

earlier, these coatings were not intentionally applied, but fortuitously

present. In the mid-30s, lens designers began experimenting with thin

deposited coatings to reduce reflection on glass surfaces that cause

flare and to correct chromatic aberrations. Coating is visible as a

coloration in the glass. On modern multicoated lenses, this coloration

is very obvious. On older single-coated lenses it is likely to be more

subtle. .

Although the effect of lens coatings was observed a couple of decades

earlier, these coatings were not intentionally applied, but fortuitously

present. In the mid-30s, lens designers began experimenting with thin

deposited coatings to reduce reflection on glass surfaces that cause

flare and to correct chromatic aberrations. Coating is visible as a

coloration in the glass. On modern multicoated lenses, this coloration

is very obvious. On older single-coated lenses it is likely to be more

subtle.

- Originally calcium fluoride was

used, and by 1940 standards it was effective, but because it remained

soft after deposition, could only be used on inner surfaces. Magnesium

fluoride was later used by Kodak. After deposition on the lens surface

it became very hard. Calcium fluoride was only used by Kodak for a few

years, beginning in 1938. If you have a camera manufactured from 1938-45,

and you see no evidence of outer coating--the lens viewed from different

angles looks like clear, colorless glass, you should probably rely on

an qualified technician--one who specializes in older optics

and is familiar with Kodak lenses--to clean inner surfaces.

- Even the harder coatings can

be damaged, either through abrasion or possibly by some chemical interaction

with cleaners or from atmospheric deposits. This kind of damage will

appear as scratches or as light spots in the coating.

- Lenses can be cleaned and recoated,

but this may not be practical except for the most expensive lenses.

|

|

|

| |

LENS DETERIORATION

- Besides scratches and coating

faults, lenses can deteriorate in two other ways.

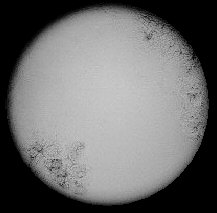

- They can be attacked by fungi,

which happens most often when they are kept in high humidity. An

illustration of fungus is shown at the right with its characteristic

webby structure. Fungi can attack the coating only or can etch the

glass itself. Fungi may be on inner, exposed surfaces or between

cemented elements. If you can remove the damaged elements and clean

the fungus from the lens surface, also thoroughly clean the mount

since spores will also hide there. Success has been reported with

ammonia, vinegar, and naphtha. Most lenses described on this site

are of simple construction with few or no mechanical linkages. They

can be completely disassembled and flooded with naphtha to expose

both the glass and mount to the cleaner. (See note above about

lenses with calcium fluoride coatings.)

- A lens with fungus damage

between cemented elements will have to be uncemented, cleaned and

recemented--probably only practical for the most expensive lenses.

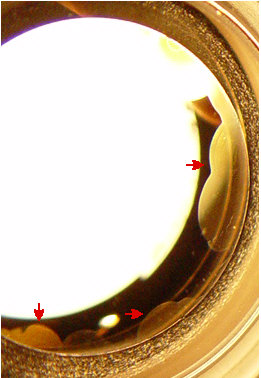

- The material used to cement

lens groups may deteriorate. In some lenses this will appear as

cloudiness, generally around the outside of the glass where the

adhesive has failed. In modern, multicoated lenses, this will generally

appear as a reflective area in an otherwise transparent element.

The best way to see this is to move a lens under a fixed light source;

the problem will be very apparent at certain angles; be sure to

look through the lens from both front and back. Lens cement can

be dissolved with acetone and new cement can be obtained, but you

must cement elements so that their optical centers coincide and

insure that no foreign material is trapped between the elements.

Most collectors will find this operation beyond their abilities

and will rely on technicians with sophisticated electronic gear

that can do accurate centering and have cleanroom conditions to

insure clean joints.

- Lenses with damaged coating

can be recoated, but again this is expensive and probably only practical

for the most expensive lenses.

- Coating problems, scratches,

fungus damage and separation will cause reduced contrast and increased

flare, generally in proportion to the placement of the flaws and

the area of the lens surface they occupy. These flaws will affect

market value to collectors and photographers, pretty much in proportion

to the seriousness of the flaws and the cost of restoration, where

that is possible.

- Store your equipment in dry,

clean, well-ventilated areas. Cameras should not be stored in leather

or cloth cases, since these materials attract fungus in humid conditions.

|

|

A lens with fungus

Lens recementing technology at Steve

Grimes' shop

A multicoated lens with

serious separation problems

|

|

|

| |

CLEANING PROCEDURE

- Begin by brushing off dust with

a camelshair or other very soft lens brush. Clean compressed

air can be used. Moisture condenses in air-compressors, however, causing

rust, and using air from such sources has the potential of depositing

debris on lens surfaces.

- If you can't get your lens sparkling

clean with air and brushing, then dampen a piece of lens cleaning tissue

with lens cleaning fluid and gently wash the surface of the lens. Lay

a piece of lens cleaning paper or tissue on the lens and squeeze one

or two drops of fluid on the paper, then pull the wet paper across the

lens. Use a mopping rather than a scrubbing technique, repeating this

operation with clean paper and fluid.

- Methanol or pure grades of alcohol

can be used as a solvent to remove oily residue; you may have to repeat

this with clean tissue and more liquid. (See Conservative View

) )

- Do not use tissue without liquid.

- I find that lens cleaning tissue

leaves fewer streaks on the glass, perhaps because it has fewer 'impurities'

than toilet tissue, so with a dirty lens, I start with toilet tissue

and finish with a sheet of lens tissue.

REMOVING LENS ELEMENTS

- Many of the Kodak lenses described

here are three and four element designs. These will usually be mounted

in shutters so that the elements screw out.

- Cameras without rangefinders

usually had front cell focusing, which depended on a threaded front

cell mounting for scale focusing. Click this link

for a new window with the procedure for cleaning this kind of lens.

for a new window with the procedure for cleaning this kind of lens.

- Kodaks with rangefinders will

have front cells that are threaded but tightened in the shutter mounting.

There are special brass and plastic wrenches used by technicians to

remove lens elements and if you have many cameras you may want to invest

in some of these. Technicians also use rubber bottle stoppers to remove

lens elements and you can find these in hardware stores. Place the clean

stopper on the rim of the lens element, press down, and turn. Make sure

you are pressing on the metal rim and not the glass. If the glass rises

above the level of the rim, you can hollow out the stopper with a rotary

tool. Never use ordinary pliers or wrenches to remove lens elements,

you will scratch the metal rim, or worse. If an element doesn't come

free with finger pressure or a rubber stopper, have it removed by a

technician. You shouldn't have to clean inner surfaces often.

LENS ATTACHMENTS

- Many highend Kodak lenses made

in the 1940s and 50s were excellent and their performance compares favorably

with much newer high quality lenses. For example look at the performance

of a ca 1940

Kodak Anastigmat Special tested by Chris Perez and compare it to

the performance of much newer and more expensive lenses on his site.

Because older lenses had less sophisticated coatings, they produce more

flare. You can reduce flare significantly by using high quality multicoated

filters and effective hoods.

- Kodak produced adapter rings

for all of their lenses. Many domestic Kodak lenses generally did not

have front cells threaded to receive screwin adapter rings. Ektra Ektars

and Medalists all use screwin attachments. Kodak screwon adapter rings

were numbered; slip-on adapter rings were measured in inches and sometimes

millimeters. Lens attachment specifications for Ektar lenses are included

in the Ektar data tables on this

site. You may be able to find Kodak or aftermarket adapter rings on

eBay or at camera shows.

- Lens caps are generally a good

thing, unless they are made from materials that can contaminate lens

surfaces and coatings. Beware cheap lens caps.

†

Kodak

Professional Data Book: Use, Maintenance, and Repair of Professional Equipment,

© 1952, Eastman Kodak

Co.

|

|

|